I always say I could write a post every day (if I had the time and technology and wanted to drive all my readers away). But it’s true: life in Zambia rarely ceases to amaze me.

I recently spent six consecutive weeks in Mfuba, consciously trying to appreciate life here and to not take the little things for granted. So I thought I’d share here some moments, both unusual and utterly typical, that together make up life in my village.

11 September

Over dinner with the Mutales, I learn that the Mfuba Co-op’s field burned – in spite of our firebreak. So much for conservation farming.

No one knows if the fire entered from outside, or if some kid lit it from inside – a common practice used to flush out bush rat if you want the uncommon delicacy of meat for dinner.

All that work: trying to get all the co-op members on board, retaining crop residues, making the firebreak … Sometimes, it’s hard not to lose hope.

Flames around the Mfuba Co-op’s field, when we were burning a firebreak in August.

13 September

I attend a wedding in the nearby village of Chisamba and note that the bride and groom both are wearing glasses. The exact same glasses that the couple who got married there last year wore. At that time I thought it unusual that BOTH bride and groom wore glasses, since almost no one here does.

Now I know that glasses are considered high fashion. People think I wear mine just for looks, and it’s become the new thing for neighbors to ask me to take their pictures wearing my glasses.

Sisters Eunice and Annie. Eunice is wearing my glasses, and Annie put them on for the next photo.

14 September

A 17-year-old boy came to my house to ask me about a hard-on he’d had for over five hours. He couldn’t get rid of it.

Only it took a long time for me to get what he was saying. He couched the whole talk by saying he’d been watching a video on a cell phone, and in the video this had happened …

I didn’t realize he was talking about himself until he showed me his penis. I am not making this up. It is shocking the trust that he and some of the other teens on our Grassroots Soccer HIV/gender team have in me.

Lee dodging “HIV risks” as part of a Grassroots obstacle course. (He is NOT the boy who came to my house today.)

15 September

Spent more than two hours waiting on the side of the tarmac road for a government official who never showed. He was supposed to come see if Ba Bernardi could be approved to keep three fast-growing goats as part of an agricultural research project. At the end of the research period, Mfuba would get to keep the goats.

Turns out the government vehicle had broken down, and no one thought this warranted giving us a call.

I raced back to Mfuba to find Ba Agatha, who’d already killed a precious chicken and was cooking it for the no-show livestock researcher. (Important guests MUST be served meat.)

She looked up from the Bemba Bible she’d been reading while waiting for us and said, “I knew he wouldn’t come.”

I was surprised, though I shouldn’t have been. She’s dealt with the Zambian Government for far longer than I.

Glancing at the Bible, I asked, “Are you looking for patience in there?”

Ba Agatha just laughed.

16 September

Attended the funeral of an old man. I’d barely known him, but here that doesn’t matter. Everyone goes. It was late in the day, so I told myself I’d sit for just 30 minutes. Somehow that turned into over an hour.

I’ve gotten very good at sitting quietly, doing nothing.

Then suddenly one woman inside the house began wailing loudly – a high-pitched, keening cry. A baby named Christopher, who’s just learning to crawl, stopped dead in his tracks. He sat down, and after a moment began to wail along with the unseen woman, with exactly the same intensity and pitch. Like he knew exactly what was happening.

17 September

Awoke from a fitful night’s sleep, punctuated by the singing and drumming that came in through my open window all night. This was the continuation of yesterday’s funeral. It’s common practice to stay up all night after someone dies.

Though I haven’t yet been to an all-night wake, today I decided, for the first time, to go to the burial. Along with the rest of the village, I followed the icitenge-wrapped casket out into the forest, to a place with several bare mounds of earth.

After some words of remembrance and some from the Bible, the men lowered the casket into the hole and began shoveling soil on top with their hoes. Everyone took a turn.

All the while – from the old man’s home to the graveyard, and during the burial – the singing went on.

20 September

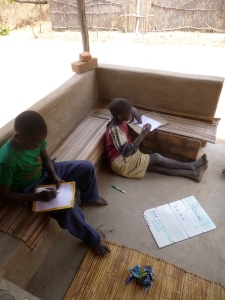

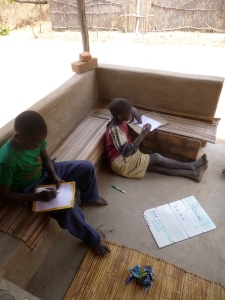

Allan Jr. and Stephen (aka Bwalya) came over to study English. This mostly means playing “Hangman” on my porch, then changing one or two letters to make new words and talk about similar word sounds.

Stephen’s current life goal is to be the one his fifth-grade teacher calls on to read English in class. Allan is only in Grade 4 but is wickedly smart. When I asked them today for words they wanted to know how to spell, Allan suggested, “discussion.” Show-off.

They got hung on that one, but only just barely. I cannot believe how much better they’ve gotten in just the past year.

Stephen and Allan Jr. patiently copying down the day’s English lesson.

21 September

I’ve got a wicked sore throat and a runny nose. Ba Allan says I’m sick again because I’ve been carrying too much water for my garden and trees. His wife, Ba Mary, blames too much bike riding for my frequent colds. Obviously, muzungus are just too weak to handle these things.

22 September

Obed, Katongo, and Boke came over to draw. I was still feeling sick, but I let them hang out a while anyway.

I happened to be low on water and didn’t feel like fetching it. I asked Boke – the oldest at eight or so – if he’d fetch me one bucketful when he finished drawing. He excitedly agreed.

Then Obed and Katongo started in: “Give us your containers!” I’m so used to people asking me for my stuff that, even though these kids rarely ask me for anything, I sighed, and started to say no. Then I realized: they didn’t want my containers. They wanted to fetch water for me, too.

Obed (foreground) and Boke are rarely happier than when they get to help me with some chore.

29 September

Upon returning from school, Boyd asked me: “Did you go to Mumana Lupando today?” (I had: to make some phone calls on the little hill where I get good cell reception.)

He – and probably most of the village – know my unusual muzungu bike-tire- and sandal-prints by heart. So they always know where I’ve been. In another place, this would be unnerving. Here, in the land where everyone asks everyone, all day and every day: “Mwaya kwi?” (“Where are you going?”), it just means they’re lookin’ out for me.

2 October

Threw up on the side of the road in Mumana Lupando this morning, right in front of all the little shops that never actually sell anything.

I’d just staggered out of a vehicle, having returned from an unexpected overnight in Kasama where I’d eaten a whole lot of rich mac n cheese, and then chocolate (things my body is no longer used to in large quantities), the night before. Probably the spectators to my spectacular, sandal-splashing upchuck figured I was hung over from drinking in town.

“What is wrong with you?” a man yelled to me in English. As is typical of Zam-English, he didn’t mean the question the way my American ears interpreted it. He was actually concerned.

Lickety-split, someone else said, “Take her to Ba Allan Mwango’s.” Ba Allan is my counterpart for all things in Mumana, which is his village. Someone took my heavy backpack, and I spent the rest of the morning lying on Ba Allan’s floor, ’til I recovered enough for us to teach the Grassroots Soccer HIV/gender club at the school that afternoon.

When we got up to leave, I noticed tiny ants had swarmed my left sandal, no doubt eating up the leftover vomit. Nothing goes to waste around here.

3 October

There’s a rumor going around Mfuba that there’s a war ku Amelika. I heard the word, “nkondo” from a dozen people throughout the day.

I e-mail my brother and learn that my home country is re-invading Iraq and Syria in response to the beheading of American journalists. I have two thoughts. First, why do all my neighbors know what’s going on in the world before I do? Second: I kind of prefer being out of touch.

6 October

Spent a solid two hours working on my bike today. Fixed a flat, changed the brakes, cleaned all the cables and the chain … Am so proud of myself I can hardly stand it. Wonder if “bush bike mechanic” is something I can now put on my resume.

7 October

This morning, six-year-old Obed came over with Gile, his two-and-a-half-year-old cousin, on his back. He was taking care of Gile while her parents went to work in their field.

I didn’t even find this unusual.

This afternoon, I ate bush rat with Boyd and Stephen. They’d caught it on their way home from school and were stoked that they’d talked the vegetarian PCV into trying it.

I could still see it’s big, rodentian front teeth.

Cultural integration complete.

Bush rat (right) and baby caterpillars, served with ubwali.

8 October

It is so hot, I wanna shoot myself. Or just lay down on the semi-cool concrete floor … Last year I was spoiled: hot season came late. No such luck this year.

9 October

Spent the day with Ba Bernardi in our district capital, Kasama, knocking on many, many government doors. Normally my absolute least favorite part of the job, this task was suddenly kind of fun when I got to share it with the headman. Bonus: TWO free rides (one in an airconditioned, leather-seated SUV!!! Unheard-of luxury!), and ice cream cones (Ba Bernardi’s first).

13 October

Biked up the steepest hill in my area in the blazing sun of 3 pm. I now feel invincible.

15 October

Today I drank a cold Coca-Cola on the side of a tarmac road, just before being magically transported the last 50 kilometers to Luwingu in a Peace Corps Land Cruiser.

It felt like a scene out of someone else’s life.

I’d biked about 30K before I stopped to wait for our new PC Zambia country director, Leon Kayego, to pass me. (He’s visiting several villages in NoPro and wants to talk to lots of PCVs.)

My bike was placed atop the cruiser, next to a big cooler. Somehow, in the excitement of giving out ice-cold beverages to everyone in the vehicle, my bike fell. The front rim is now so bent that Adam and I had to remove the front brakes so I could still ride it the 20 kilometers from Luwingu to Jesse’s village of Kuta (where Ba Leon would later meet us).

The wheel wobbled all the way there, and all the way back to Mfuba the next day.

Somehow, this is exactly what I’ve come to expect from my Peace Corps service: moments of great, unexpected joy resulting from the smallest of luxuries, followed immediately by a great big f*** up that turns out to be not such a big deal after all.

16 October 2014

I return to Mfuba to the smell of rain. Heading in from the tarmac, there are puddles instead of sand traps, ripples and waves imprinted by running water.

I bike through clouds of just-emerged winged termites, thinking, ah, I JUST missed an early rain! Then, a few kilometers from home, big, cold drops begin to pelt my salty-grubby skin. After two sweaty days of bike riding, I feel refreshed and alive.

18 October

Early this morning, I found Stephen working away in my field. When I hadn’t found him at home at 5:45 a.m., I assumed he hadn’t left the house yet. Wrong. He was already working on the tilling we’d begun a few days before.

As I approached, I could see him digging away – deliberately, patiently, the way he does most things.

I apologized for being late, but he smiled and said, “Mwisakamana.” (“No worries.”)

Suddenly, I was filled with so much love for this cocky, grubby, funny teenager that I felt my heart might burst.

Stephen tilling my field.

20 October

It’s only 7:15 a.m., and I hardly know what to do with myself.

We got our first BIG rainstorm last night. (It rolled in just as Stephen and I were heading to his place for dinner. We were on the path under my umbrella when, all at once, he yelled, “Run, Ba Terri, run!” and was off.)

This storm came much earlier than last year’s first big one, and about five days earlier than normal.

So, all of a sudden, everyone in Mfuba is out tilling their fields or gathering caterpillars. I finished prepping my tiny parcel with Boyd and Stephen two days ago, and I don’t eat caterpillars.

I’ve patched the small leaks in my roof with duct tape. Ba Bernardi says he’ll come over this afternoon to inspect the roof of my porch, which became a small lake last night.

Patch job on the inside of my roof. (Thanks to all those who’ve sent me duct tape – especially the Superman tape!)

I certainly don’t need to water anything today, so there goes my usual hour of fetching and hauling 90 liters. No more constant vigilance against goats and chickens, either.

For my neighbors, work now begins in hyper-drive. For me … It’s probably just as well that I go on vacation in two days.

21 October

This morning I received my first chicken, then five minutes later watched Ba Allan nearly get killed by an angry cobra. All before 7 a.m.

It’s gonna be a busy day.

And not only for me. The whole village is getting ready for an important visitor. Ba Henry, my fantastic Peace Corps boss, is coming to talk with the community about my – ulp – replacement.

The activity began at 6 a.m., with my neighbors split into three groups. One group went to work in the community demonstration field; one began building a raised platform in their (soon-to-be, we hope) goat shelter; and one came to my place to fix my falling down bathing shelter and to make the path to my house look presentable.

Ba Juliet, Ba Miriam, and Banakulu Mishek, prepping the community demonstration plot.

Then of course there was Ba Agatha, cleaning and cooking away all on her own.

Nothing like a big wig visiting to inspire people to work!

The chicken and the snake, well, they were just coincidence. The former was a trade I’d been waiting on for nearly a year and had frankly given up on receiving. Of course I got her the day before I leave for vacation. I’ll have to rely on Boyd and Stephen to feed her while I’m gone …

The latter Ba Allan and Ba Bernardi found in the goat shelter. A far more exciting experience than the last snake execution I witnessed. Allan and Bernardi had only bricks and a couple of sticks, and the snake was tough to corner in the darkness of the windowless building.

It was kind of terrifying watching the guys throw a brick or jab a stick at the snake, then jump back out of the doorway.

But in the final act, I really thought Ba Allan might get bitten! The cobra came through the crack between door and door jamb, hood fully flared, fangs bared, spitting venom for all it was worth. Ba Allan, armed only with a long stick, took several blows to kill it.

Ba Allan killing a cobra with a stick. You can just make out the snake in the crack of the door where he’s jabbed the stick.

Kinda terrifying. So scary, in fact, that I stopped taking photos. But the image will remain forever imprinted on my brain.

What a way to start a big day.